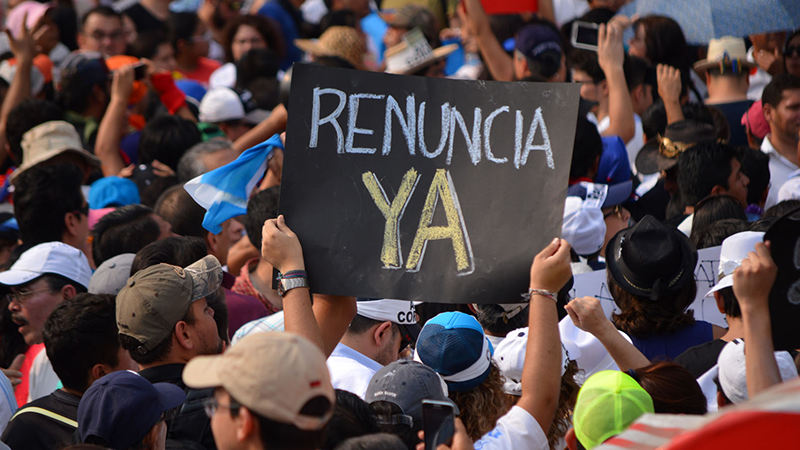

Protesters insist corruption and human rights issues need to be addressed

– A corruption scandal reaching up to outgoing President Otto Pérez Molina threatens to derail democratic rule in Guatemala ahead of the presidential election scheduled for September 6.

Having announced on national television that he will not resign, Pérez Molina is resisting popular protests demanding that anti-corruption reforms be passed before the next election is held.

Sadly for the impoverished Central American nation, the spotlight during the campaign season has been on the corruption scandals rather than on what candidates will do to reduce poverty and increase opportunities in the country with the largest indigenous population share in Latin America.

With 16 million people, Guatemala is the most populated country in Central America. With more than 55 percent of the population living below the poverty line, the fastest growing country in Latin America is poised to surpass both Ecuador and Chile’s population by 2020, when its population will reach 20 million.

With the sixth lowest Gross Domestic Product per capita in Latin America — above Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Guyana — Guatemala adds 450 thousand new people to its population every year, most of them destined to a life of poverty and destitution.

Although corruption is endemic in Guatemala, a bigger than normal scandal exploded earlier in 2015 associated to a customs corruption scheme that forced the resignation of the vice-president in May and has extended to implicate high-level officials in the executive, the legislature and judicial powers. Independent prosecutors and civil society organizations have struggled to denounce abuses that affect low income families and divert government funds to private pockets of dishonest politicians.

The corruption scandal has overtaken the presidential election campaign. With four months remaining in his term, Pérez Molina is more preoccupied with the scandal not forcing his resignation rather than with who will succeed him.

Though there are 14 presidential candidates, only four have a chance of becoming president. If no candidate wins a majority on September 6, a runoff will be held between the top two contenders on October 25.

The front runner is Manuel Baldizón, a 45-year-old lawyer and businessman first elected to Congress in 2003. In 2011, he ran as the candidate to succeed outgoing president Álvaro Colom, a moderate leftist who only supported him after the Supreme Court banned the president’s wife from running.

Baldizón lost, but built a platform for 2015 as the head of LIDER, a personalist party. Because some of Baldizón’s allies have been involved in corruption scandals, he is the candidate most closely associated with the culture of corruption so prevalent in Guatemala today.

Jimmy Morales is a 46-year-old businessman who has hosted a popular television show for 15 years, Moralejas. With a politically ambiguous discourse that utilizes populist rhetoric, Morales would be the government’s preferred candidate, but he is also perceived as being too cozy with the special interests that have captured government institutions.

There are two women among the front runners, Sandra Torres, the wife of former president Colom and Zury Ríos, the daughter of a former dictator in the 1980s, Efraín Ríos Montt. As the first lady from 2008 to 2012, Sandra Torres became a national figure.

Corruption accusations against her left-leaning husband hurt her and her failed attempt to bypass a constitutional ban on presidential relatives from running for the presidency by divorcing, but not formally separating from Colom.

Zury Ríos has other problems to deal with. Her association with allies of her father bring back memories of human rights violations against indigenous communities, but her tough stance on crime also attracts support among the vulnerable low and middle class.

Though polls are not very reliable, the expectations are that Baldizón will face Morales, Torres or Ríos in the runoff. Whomever wins, corruption accusations will still dominate the political arena.

As all the frontrunners are associated with corruption scandals or human rights violations, a growing segment of civil society, including many independent journalists, have called for the elections to be suspended and for profound anti-corruption reforms to be implemented before the democratic process can be resumed.

Among some of the changes to be adopted, a ban on party switching among legislators (a common practice, even among presidential candidates, that limits accountability), campaign finance reform and other anti-corruption measures would be required steps before meaningful democratic elections can be held. The demands are reasonable, but difficult to implement. If the entire institutional setup is affected by corruption accusations, who will implement the needed changes?

Though events are fast unfolding in Guatemala — with rumours of a presidential resignation forcing a televised national address by Pérez Molina this past Sunday to assert that that he will serve until the end of his term — it seems unlikely that elections will be delayed.

Turnout is expected to fall below the 60 percent mark of 2011, with most non-voters coming from low income urban areas; rural turnout is higher due to vote buying. Guatemalans are upset and disappointed, but there is no easy way out. If elections will not save democracy in Guatemala, it is hard to imagine what will.

What People Are Saying